Polarization challenges Return Day traditions

by Andrew Sharp, Delaware Journalism Collaborative

This story is part of the Delaware Journalism Collaborative, a partnership of local news and community organizations working to bridge divides statewide. Learn more here.

GEORGETOWN — You have to wonder: In these days of deep political anger, how wise is it to let opposing politicians stand together near a weapon?

That’s what Delaware does after every election. It’s the tradition of Return Day, and the weapon in question is a hatchet buried by the opposing sides in a reenactment of the old metaphor.

Democratic and Republican politicians from the governor to senators to local town council members gather for a parade, feast and speeches, riding in carriages together in a demonstration of goodwill.

It’s not perhaps a sign of affection but at least a token of willingness to work together for the good of the state and a reminder that, though they’re opponents, they don’t have to be enemies.

“It means, kind of, the essence of how politics should be,” said Republican state Sen. Brian Pettyjohn, who represents the Georgetown area. It’s “the beginning of us as elected officials actually getting to work for the people that elected us. And to put the partisanship aside.”

That’s the idea anyway.

But this year, a note of discord has crept in. The Delaware Democratic Party Executive Committee has called on its candidates not to ride in some of the carriages used in the parade. Why? The antique vehicles come from the Nutter D. Marvel Carriage Museum, which is under fire for a Confederate battle flag flying above a memorial to Delaware soldiers who fought on the Southern side in the Civil War.

Some question the Democrats’ move as going against the very spirit of the event, while others emphasize that people of both parties are taking a stand against the flag, while still enthusiastically participating in Return Day itself.

The dispute over a flag flown in a war more than 150 years ago is just one of the many fights that have split communities in the United States in recent years. It’s also a chilling reminder of where such polarization can lead.

Politicians and their followers have been smearing each other since the beginning of the republic, but many observers agree that the trend has swung back toward the extreme side in recent years.

“Our politics really started to become a blood sport in the early ’90s after the Clinton election,” said Niklas Robinson, an associate professor of history at Delaware State University. He also mentioned the 1994 midterm elections, when Newt Gingrich launched a national rallying cry for the GOP with new political strategies and more disciplined messaging.

In the past, major events like World War II may have brought people together, albeit imperfectly, Mr. Robinson said. But the most recent crisis, the COVID-19 pandemic, only served to drive people further apart.

“It’s increased everywhere. And, unfortunately, we’re seeing that increase (in polarization) in Delaware, as well,” Sen. Pettyjohn said. The division is trickling down to the local level, from state races to town elections.

“You’re starting to see those divisive issues come into more of the local politics, where it shouldn’t be. And it’s taking the focus off of these races where there’s … very important local issues to be discussed.”

Further, we’re “relying on proxies, relying on media, relying on social media, … relying on labels, instead of listening to people’s stories,” said Joe Lawson, a member of the Southern Delaware Alliance for Racial Justice.

The turn of the millennium, just after the bitterly contested impeachment proceedings for President Bill Clinton, was not an oasis of cheery political cooperation. But compared to now, it can spark nostalgia. Marilyn Booker, president of the Sussex County Republican Party, recalled the days after the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks, when members of both parties gathered on the steps of the U.S. Capitol and spoke in a unified voice. Today, “I don’t know that we would come together if we had some type of a tragedy like that,” she said.

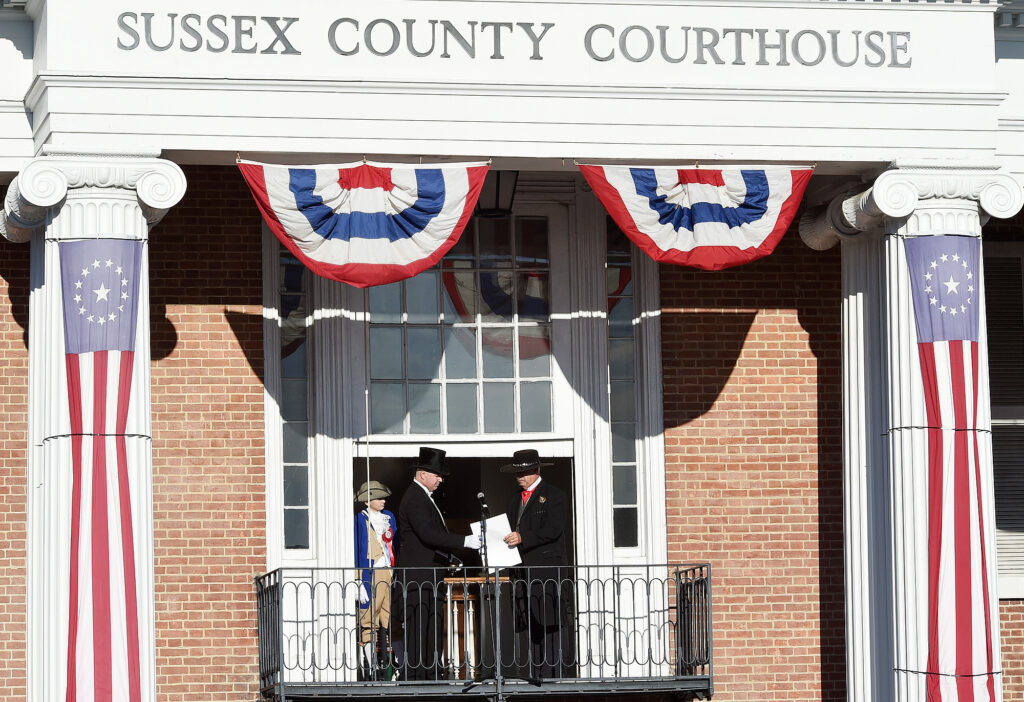

Sussex County Sheriff Robert Lee, right, hands the election results to Georgetown Town Crier Kirk Lawson as Sussex County Return Day in 2018. Special to the Delaware State News / CHUCK SNYDER

Is polarization always bad?

Friendship and unity are appealing, but what about fights worth having?

This tension came up quickly in conversations with observers of the Georgetown dispute, as they spoke of the importance both of working together and sticking up for important principles. Battles over values, of course, are often at the heart of division, whether it’s a Civil War flag, abortion or capitalism.

“It’s become increasingly clear that there are certain things that people don’t want to compromise on,” said Travis Williams, executive director of the Delaware Democratic Party. “And if the Confederate flag is one of those things … acknowledging the humanity of certain members of the community, that’s not something I’m willing to compromise on.”

For its part, the Sons of Confederate Veterans organization behind the flag and memorial sent a written statement to the town of Georgetown earlier this year, decrying “an ugly ‘cancel culture’” and “modern day bullies,” and quoting civil rights activists who they say had no problem with the flag.

When it comes to civil rights, conflict was instrumental. Mr. Robinson noted that hundreds of thousands of people died in the Civil War, and thousands of African Americans were lynched in the more modern civil rights movement.

Polarization and division are not necessarily the same, though, by polarization, people often mean hostility. On a basic level, polarization could be described simply as the parties becoming more clearly defined by ideology, as the journalist Ezra Klein argues in his 2020 book, “Why We’re Polarized.” People within the parties line up more closely with that ideology, like metal shavings sharpened into a line by a magnet. In fact, Mr. Klein cites political scientists in the 1950s who were deeply concerned that the parties were too similar, giving voters no real choice.

“Division is natural, right, and that’s instrumental to any sort of vibrant, healthy, democratic dialogue between different groups,” Mr. Robinson said. Polarization and party politics have been embedded in the system since the beginning.

But, as most people use it, the term “polarization” has come to mean extremism. It’s “the digging in of heels and refusing to be moved by any sort of counterargument,” Mr. Robinson said. The polarized extremes “really play on people’s emotions and fears, as opposed to motivating people to think and learn.”

“That is the way we believe from one side to the other,” said Carlos de los Ramos, chairman of the Delaware Hispanic Commission. “Republicans take over, they’re going to destroy this; Democrats are going to take over, they’re going to destroy, so we vote party lines.”

You’d be a fool to compromise with someone who is out to destroy you. From that vantage point, it’s logical to see opponents as bad actors who can’t be trusted. And what makes it tricky is that, sometimes, under the rhetoric, there really are bad actors, and, to figure out who they are, people have to sort out politically motivated exaggeration from the truth.

“It’s difficult to compromise with folks who are not coming to the table in good faith,” Mr. Williams said. A significant portion of the GOP doesn’t want to do that, in his opinion. He referred to those who don’t want to acknowledge the results of the 2020 election.

“We are all Americans, all Delawareans. We’ve got to come together,” Mr. Williams said. “But if we are being asked to compromise with folks who don’t want to compromise, frankly, or are trying to break the system, then I’d have a hard time coming back to the table with those folks.”

There’s no shortage of conservative commentators distrustful of those on the left, either. Talk radio hosts have made careers out of peering inside the brains of Democrats and exposing their sinister motives to destroy American democracy.

The risks of polarization

If you disagree on a host of major issues and don’t share common goals — or don’t think you do — it’s easier to hate people on the other side and view them as dangerous enemies, as Mr. Klein notes. He says when our identities become tied up in our parties, every election feels like a must-win crisis.

Candidates, too, can treat their opponent as an enemy or object to be defeated, Sen. Pettyjohn reflected, rather than as a fellow member of the community — one with a different point of view — who wanted to get into politics and have a voice.

“Unfortunately, that divide between political points of view are really taking over our homes, our daily lives … because you have an R or a D on your chest, (and) that’s why I don’t like you anymore,” Mr. de los Ramos said. “And so that needs to change.”

Attacks from the other side certainly don’t make them feel warmer toward each other.

“Immediately, people go to their corners, and they start demonizing the other person on personal issues,” Ms. Booker said. “Because I have an R after my name, I’m considered to be a racist, and I don’t appreciate women or don’t want to support women.”

“To continue in this direction is going to destroy us,” Mr. de los Ramos said. “I can see people from the outside laughing at us and waiting for this empire to crumble because this is exactly what’s going to happen if we continue … hurting each other.”

What’s causing it?

Ask why our divisions are becoming more extreme, and some common themes quickly emerge, centered on how and why we get our information.

Interest groups pour an incredible amount of money into American politics, Mr. Robinson said, with billions of dollars being spent on the upcoming midterm elections alone.

Division is fed by disinformation, like wild conspiracy theories, and by ready access to news that supports a particular point of view. “We have media outlets that are either really far to the right, in the case of Fox News, or really quite far to the left like MSNBC and the Huffington Post,” he said.

Mr. Lawson also pointed to the media as contributing to the problem.

“I think that some of the things that media does to just get headlines and ratings,” he said, “they’re very good at getting people’s attention, to getting people angry, but not at getting people informed or at least seeing the honest human part of a disagreement.”

Mr. Robinson referred to wild conspiracy theories like QAnon that circulate on social media and also the huge impact these platforms have had on politics. “When you have the ability to just throw out a tweet or a Facebook post, and it goes to hundreds of millions of people in an instant, it’s just uncharted territory.”

Misinformation and big money combined, Mr. Robinson said, are very destabilizing.

Increasingly, we have replaced personal connections with online interactions. People aren’t listening to each other, Ms. Booker said. “And there’s no ability to get your point across or be able to talk with other people.”

“I don’t know how you change that culture, to have people engage in proper face-to-face discussions,” Mr. Robinson said. As a historian, he can weigh in on what has happened but doesn’t have a lot of answers on how to fix things. “In 50 years, 100 years, people will look at this moment — moments — and wonder what the hell people were thinking.”

Ox sandwiches, a Return Day tradition, were passed out in 2018 on The Circle in Georgetown. Special to the Delaware State News / CHUCK SNYDER

Finding common ground despite real differences

Look closer at the dispute over Return Day, and you’ll find that it doesn’t fit neat partisan boundaries.

Take Tom Marvel.

The Georgetown resident recently penned an op-ed about his grandfather, Nutter Marvel, whose estate formed the basis of the Marvel Carriage Museum at the center of the flag controversy. He was concerned that newer residents of the county might not know who his grandfather was and would associate his name with the Confederate flag.

Mr. Marvel is strongly opposed to seeing the flag displayed at the museum while it bears his family name, and he says other members of the family agree. It’s a symbol of slavery and flies in the face of the Black community in Sussex County, he said.

On the other hand, he also thinks candidates refusing to ride in the carriages is absolutely not in keeping with the spirit of Return Day. “It’s very disappointing, but I can see their point if that’s their belief,” he said.

So, for those keeping score: While it’s the Democratic Party calling on candidates not to ride in the carriages, Mr. Marvel, a Republican, is criticizing both sides. Georgetown Mayor Bill West, also a Republican, told the Daily Beast that he will walk instead of ride in the carriages this year.

Another prominent Sussex Republican, County Councilman Mark Schaeffer, blasted the display at Georgetown, saying it had no historical value and was a celebration of “the treasonous and racist Confederate movement,” the Cape Gazette reported.

The Return Day disagreement illustrates the tension between calls for more unity and understanding, and opinions on issues participants feel deeply about. Those who spoke against the dangers of polarization for this article also disagreed, sometimes bluntly, about the Return Day situation. At the same time, they shared many of the same sentiments about the importance of the event.

Mr. Williams emphasized that candidates who skipped the Marvel carriage rides would still take part in the rest of Return Day.

Coming together after the election is important, Mr. Williams said, “a reminder that we’re all in this together. And that’s why we are still expecting to participate.”

Amid the strong feelings, there can still be conversation.

Mr. Lawson spoke of his “conservative buddies,” some of whom disagree with him about the Confederate flag. He likes and respects them anyway. They try to convince each other, but they know “we care about America, we care about other people. And even if we disagree, we can see that.”

In the current climate, Mr. Lawson said, there’s a belief in “some people not caring about America, hating America — ‘woke libs.’ You know, conservatives that want to destroy the country. That’s not who these people are. That’s not who I am.”

Mr. Marvel dealt with the same tensions. He spoke passionately about his opposition to flying the Confederate flag. He also recalled running into an old school friend at a convenience store recently, who said he didn’t understand Mr. Marvel’s stance on the flag because the Confederate flag is not about slavery. The war, his friend contended, was about states’ rights. Mr. Marvel strongly disagreed, but said, “You have your opinion. I’m not going to try to change it.”

To handle disagreements like this, Mr. Marvel’s approach is, “You’re my friend, and you’ve always been my friend, but I completely disagree with you, and I’ll just leave it at that.”

Ways to begin breaking out of the hostility

In the past in the United States, Mr. de los Ramos said, people in politics came together for a healthy discussion, and afterward, they shook hands and moved on. He admired that.

“That is not happening anymore,” he said.

Like Mr. Marvel and his friends, can we find a way to disagree without being enemies?

“Not one party has cornered the market on good ideas. And no one party has cornered the market on bad ideas,” Ms. Booker said.

She wants to see better leadership and says we’re plagued by power-hungry people using the legislative process as a weapon, and its effects are showing up in our communities.

“I want statesmen in (the) White House; I want statesmen in Congress, … and I want them in our General Assembly,” Ms. Booker said. There are some, she said, but “they’re being quelled. They can’t get their word out.”

Mr. Robinson feels we also need a revival of understanding — the historical, political and social origins of modern America — so we will be less vulnerable to conspiracy thinking.

The need for better community connections and conversation was a common idea for improving the situation.

Even among those unbothered by the Confederate flag, Mr. Lawson said, “virtually no one is saying slavery was good. So let’s try to initiate conversations where we can have some things that we agree on. And in the case of Return Day, we all agree Return Day is a magnificent tradition that Delaware has.”

He’d like to see churches and government entities provide forums for these conversations.

It doesn’t often happen that people are willing to listen to the other side, to sit down and have a conversation, and give the other person an opportunity to finish their sentence, Ms. Booker said.

“We can’t get anything done unless we can communicate with each other.”

“It’s important to keep in mind that we are all, should all be, rowing in the same direction,” Mr. Williams said. Delaware is a small state, sort of like a statewide small town, and opponents will cross paths.

“You’re going to interact with people on a regular basis. And even if you disagree with them, you’re still going to have to go work with that same person, see them at soccer practice. … I think a lot of times when folks feel polarized, it’s when those connections, those everyday interactions aren’t as present,” he said.

Sen. Pettyjohn promotes more compromise and says face-to-face communication is best. “We can only find a solution to the problems that we have by coming together, both sides, and listening to each other and trying to work out something that’s … somewhere in the middle.”

As opposed to sniping on Facebook or Twitter.

“Stay off social media,” he said. “I don’t know very many social media posts where you actually move the needle in terms of changing somebody’s mind.”

Polarization involves a complex tangle of related issues. Given the stakes, a collaboration of news outlets around the state has launched a two-year effort to unravel some of those issues and to explore solutions for a better community. In the coming months, look for stories on the topic from the new Delaware Journalism Collaborative, from articles to radio coverage and videos, along with community forums and other resources.

Working together, outlets can accomplish more and do it better, according to Allison Taylor Levine, president of Delaware’s Local Journalism Initiative. Ms. Levine spearheaded the idea for the collaborative.

“We’re at a place in our history when many of us have stopped working together and started working against each other, instead of working in the best interests of our communities,” she said. “And I think we all realize that’s not doing anybody any good.”

She hopes the collaborative will help people start listening to each other.

“I hope that we all start to recognize that people are complicated and add value in lots of different ways, even if we disagree on some big points.”

Read more

History of Return Day: From politics to parties, the tradition dates back to 1812

How do people feel about Return Day? In upstate, there’s an overwhelming silence

Main photo: The Hatchet is buried with Don Petitmermet, Jane Hovington, Wolfgang Von Baumgart and James Brittingham as Sussex County Return Day was held in Georgetown on Thursday November 8th with politicians “Burying the Hatchet” to end the 2018 Election.

Special to the Delaware State News / CHUCK SNYDER